When radicalised terror offenders are released from prison, how should they be dealt with?

Two recent attacks in London have brought the question into sharp focus because both involved extremist offenders carrying out knife attacks despite being on the radar of security services.

Sudesh Amman, 20, carried out the Streatham attack last month only 10 days after his release from jail. It was a case that reverberated across Europe, where other offenders will soon be freed.

The UK quickly passed legislation to block the automatic early release of convicted terror offenders. Other European countries are grappling with the same balance between security and civil liberties. For terror offenders, a second chance comes with many strings attached.

How many terror offenders are there?

Hundreds will be released from European prisons within the next few years, figures suggest. Europol, the EU’s law enforcement arm, gives an idea of the numbers.

- Sudesh Amman: Who was the Streatham attacker?

- London Bridge attacker completed untested rehabilitation scheme

- EU struggles over law to tackle spread of terror online

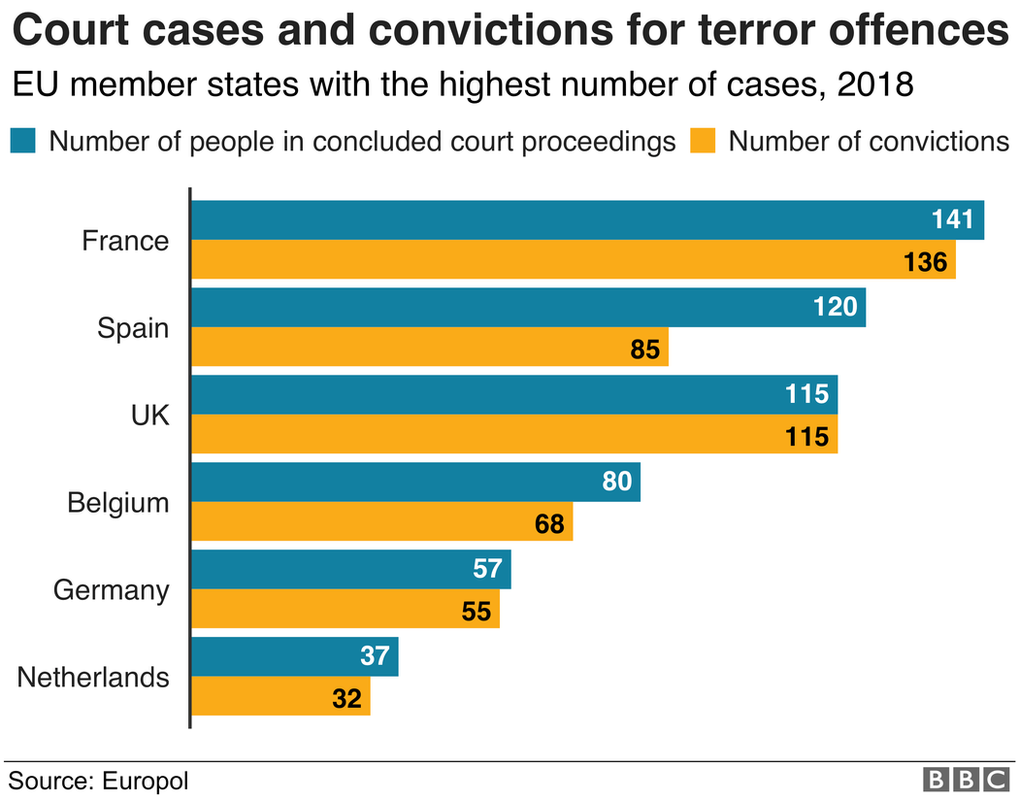

From 2016 to 2018, Spain had the most court cases for terror offences (343) in the EU, followed by the UK (329), France (327) and Belgium (301).

In 2018, 61% of verdicts for those cases in EU states were classed as “jihadist terror offences”. This verdict trend, Europol said, started in 2015 – a year after the Islamic State (IS) group declared its caliphate in the Middle East.

Radicalised by IS, jihadists carried out a series of atrocities. The November Paris attacks in 2015 claimed 131 lives and the Nice lorry attacker murdered 86 people in July 2016.

Terror offenders do not stay behind bars forever – a point underlined by Globsec, a think tank. Of 199 individuals arrested for terror offences in 2015, 57% would be released by 2023, it said. Their offences range from planning attacks and membership of a terrorist group to financing terrorism.

In France alone, around 45 of the more than 500 terror offenders in jail are expected to be released this year. In the UK, the number is 50, in Sweden it is zero.

Most European countries run or fund rehabilitation programmes. These are mostly small-scale programmes focused on a limited number of offenders. They can be mandatory or voluntary.

Some aim to change the behaviour of offenders – which is known as disengagement; others seek to overhaul their ideological outlook – called deradicalisation. The process typically starts in prison, where inmates are considered vulnerable to radicalisation.

How Germany tries to deradicalise its offenders

Violence Prevention Network (VPN) is just one of the numerous civil society groups dealing with the deradicalisation of extremist offenders in Germany.

When it was founded in 2001, VPN dealt with few serious terror convicts. Young offenders at risk of right-wing extremism were its target group.

That changed in the mid-2010s, when Islamist fighters started returning from war zones, bringing their extremist views into prison with them.

“These individuals are so dangerous, you can’t train them in a group,” Cornelia Lotthammer, a spokeswoman for the VPN, told the BBC. “There’s always a risk that the group will be manipulated.”

More from Source:https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51560046